The economy of Japan while its economic might is still widely respected…. These days, the western world largely fears the rise of another Asian giant…

But, as it so happens, in 1989, the year that I was born, the world was simultaneously fearful and in awe of the rise of the magnificent Japanese economy. So…. What the hell happened? How did the economy of this Asian archipelago, which came so close to overtaking America as the number one economic superpower, end in deflation and stagnation?

I mean, by now it’s gotten so bad that the Bank of Japan, in a desperate attempt to turn this situation around, has bought up to 70% of government debt and has even become the biggest shareholder of corporate Japan.

If you prefer to consume this story in video format, check it out here:

The bubble to end all bubbles: 1979 – 1990

Alright, this story starts on a high note. The eighties, when Japan was still a growing economic superpower.

The response to the oil crisis

Okay technically, this story starts in 1979, the year of the second oil crisis, which was caused by the Iranian revolution and subsequent war between Iraq and Iran. To save their economies from the fallout, all major industrialised nations, including Japan, responded by lowering their interest rates.

This marked the start of easy monetary policy in Japan and it set the scene for one of the biggest asset bubbles of all time. But, this was not immediately obvious. After all, nationwide bubbles take a long time to develop, and they might start in the form of a healthy, productive economic boom.

Indeed, the Japanese economy of the early 80s was characterized by massive investment in research and innovation, partially made possible by these low interest rates. But, also by a little-known secret monetary technique known as window guidance.

You see, unlike Western central banks, the Bank of Japan had a very innovative way to create credit in the right strategic industrial sectors.

How it worked was actually quite simple. The Bank of Japan would simply go to Japans biggest banks and give them a quota. This meant that it told them, create this much credit for the steel industry, create this much for the automobile industry, and this much for the shipbuilding industry…

And, I know, I said it was a secret technique, but it wasn’t that secret because these quotas were printed in major Japanese industry magazines. But, it was a secret is the sense that the technique of window guidance was never really picked up by mainstream Western economists and that is why you have probably not heard about it before.

I suspect that the reason is that it was incompatible with the free market economics that dominated the economics profession at the time.

However, one group of central bankers were paying close attention to the practice of window guidance and those where the Chinese. But, that is a story for another video.

The American - Japanese trade war

Back to Japan, whose industries seemed unstoppable.

So much so, that the United States feared that Japan was going to overtake them to become the number one global economic power. Especially, fearful of the destruction of the American car manufacturing industry, American workers flocked in droves to Republican president Ronald Reagan who pledged to do something about the trade deficit with Japan. And that, he did, first in 1981 he limited the number of cars that could be imported from Japan every year. And then, in 1983, he slapped a whopping 45% tariff on Japanese motorcycles, reportedly to save American motorcycle icon: Harley Davidson.

But, in stark contrast to the current trade war between the US and China, something remarkable happened in 1985.

This is the year of the so-called Plaza accords, in which European, American and Japanese politicians agreed that global trade was imbalanced and that the Dollar was too expensive compared to the British Pound, French Franc, Deutsche Mark, and most of all the Japanese Yen. And so, in these accords, the Bank of Japan promised to sell massive amounts of its Dollar reserves to make the Yen appreciate and to depreciate the dollar in the process.

And… it worked!

As you can see in the graph below, after the Plaza accords the Yen started rising against the U.S. Dollar and while this proved troublesome for Japanese exporters, Japanese consumers saw their relative wealth skyrocket thanks to cheaper imports. However, to counter some of that upward pressure on the Yen, the Bank of Japan lowered interest rates even further. The side effect of this was that, with borrowing even cheaper, the scene was set for one of the craziest nationwide bubbles of all time.

Now, there is a popular argument that it was through these Plaza accords, that the United States was ultimately responsible for the Japanese bubble and subsequent destruction of its economy.

I have to say, I find that argument unconvincing since the Bank of Japan could have easily have cooled down the bubble with stricter rules on lending or through window guidance. The bubble

The bubble

Still, low interest rates definitely contributed to the late 1980s bubble period, in which both property and stock prices went through… the… roof. So much so that it was estimated that at the height of the bubble the small plot of land, that the Kyoto Imperial palace sits on, had a higher valuation than all of California’s real estate combined. And since all Japanese citizens appeared to become rich simultaneously during the bubble, Tokyo became the party city of the world where businessman would spend cash freely on champagne and exotic dancers. Furthermore, with the Yen riding high, Japanese investors flooded the world, buying up famous New York landmarks such as the Rockefeller Centre and U.S. companies such as Columbia film studios.

But, the Bank of Japan was not blind to the possibility of a bubble. In fact, if you dive into their records, you will find several mentions of bubble risks during this period. However, it was all talk and no bite. It was only in 1989, that the Bank of Japan started to raise interest rates.

And that …is what finally popped the bubble, marking the peak of the Japanese Stock market, property market, and indeed the mighty Japanese economy itself.

And while the Bank of Japan did not realise it at the time, in hindsight, this was the moment when the Japanese econony turned from miracle economy and fell into the arms of stagnation and deflation.

But, as it turns out, what drove deflation in the next three decades was the interaction of multiple economic mechanisms. Conveniently, the three most important mechanisms can be divided into three periods that largely overlap with the three following decades:

- Debt-deflation in the 1990s,

- The inflation expectations trap in the 2000s, and

- population decline in the 2010s.

Let’s start with the 1990s.

Debt-deflation: 1990s

The first decade of Japanese deflation was also its most dangerous because it was characterized by a volatile combination of debt deflation and a banking system on the verge of collapse.

Debt deflation

The term debt-deflation was coined by famous U.S. economist Irving Fisher around the time of the great depression in the 1930s. The basic mechanism is the following. Picture a debt-fuelled housing bubble that has just popped. With house prices falling, most people are now left with both a massive mortgage and a massively devalued house. This house can no longer be sold to completely repay it. Therefore, if people want to move, they will be forced to repay their debts the old fashioned way, by tightening that belt buckle and buying less stuff. Now then, obviously, the overall demand for stuff will decline. However, the supply of stuff is still the same. After all, all the factories are still there and there are plenty of workers looking for a job. And so, since the overall supply of stuff is bigger than the overall demand for it, on average, the price of stuff… will drop. This… is deflation.

What Irving Fisher recognized is that, when people are highly indebted, deflation will make it even more difficult for them to repay their debts because the value of their debts will remain constant prices, and therefore the way people might earn an income spiral downwards.

This, of course, means that struggling borrowers will spend even less. Meaning that incomes decline even further, debts become even more difficult to repay and hence more deflation follows. To break this vicious cycle, Central Banks will need to act forcefully. For example, by decreasing interest rates to help the struggling borrowers out of the deflationary spiral.

And it was with this in mind that the Bank of Japan did cut interest rates in 1991. But only by a little.

In hindsight, it did not fully recognize how big the bubble had really been. So, it was too little too late.

Debt deflation had taken hold, and prices kept dropping throughout the 90s, while the Bank of Japan kept cutting rates, slowly, vainly trying to break this vicious cycle.

A banking system on the verge of collapse

But, that was just the start of Japans problems. Because not only had its borrowers gotten into trouble, This is also when, Japan ran into a second economic feedback problem and that is the one between banks and the economy. You see, a faltering economy makes it less safe for banks to lend to the companies in it. And less credit for these companies means less investment, and hence a faltering economy. At this point, it became increasingly clear that the Bank of Japan needed to take swift action to re-capitalise the banks so that they would start lending again. And … again, it did… carefully.

That is, if you consider injecting billions Yen into faltering financial firms, being careful. The public certainly did not consider it careful, given that this created quite a bit of backlash.

Why should the government rescue banks? And actually, I get that, I even agree with that sentiment on moral grounds. However, the problem for central bankers is that banks provide an essential economic service… money creation… So, even though banks should be held responsible for their role in blowing the bubble, if you let them fail… you might have the moral high ground. But, also an economy that is completely destroyed.

But yeah, that being said, there was a strong public backlash against bank re-capitalisation and this made further rescues infeasible. As a consequence, the banking sector remained in a slow downward spiral…

A spiral that came to a spectacular conclusion during the dark days of November 1997 which marked the start of Japans banking crisis. This came as a shock since, while most of Asia had been in the grips of the massive Asian financial crisis that had started in July 1997, Japan and the Yen seemed to have weathered this storm rather well thanks to the Bank of Japans massive war chest of foreign reserves that had been built up using the proceeds of Japans consistent trade surpluses.

But then, on the morning of November the 26th 1997 the phone rang at the ministry of Finance. It was the Bank of Japan.

The message was simple: “lines are forming in front of the banks.”

This is when it truly sunk in, 7 years after the bubble had popped, Japan had its second moment of reckoning as it found itself in a full-blown banking crisis. This was especially problematic since the Bank of Japan was not able to cut interest rates further since they were already at 0%. So, in a desperate move to stop the panic, Japanese officials instructed the banks to let in as many customers as possible. After all, lines in the street would attract unwanted attention that might spill over into a nationwide panic and subsequent run on all banks.

However, the move was in vain, the media was already aware of the lines.

But, then, something happened that, I think, could only happen in Japan. Or, let me put it like this, it would never happen here in Europe.

The news media, universally, without pressure from each other or from the government, decided that it would be in the best interest of the nation… to just … not report on this.

And so, in the afternoon, word reached the offices of the Bank of Japan that the lines in front of the banks had all but disappeared and a true panic had been averted. Now, that doesn’t mean that a financial crisis was averted. All in all, in 1997 and 1998, 7 major financial institutions failed and the banking crisis only came to a halt when, in spite of public pressure, several financial institutions had been saved with tax payer money.

However, one silver lining was that this painful banking crisis, finally got rid of the debt legacy of the asset bubble. Debt deflation was finally over and the Japanese banking sector was ready to support a resurgent Japan as it entered the 21st century.

The inflation expectations trap: the 2000s

However, as we all know now….. this did not happen. Instead, Japan found itself once again in a deflationary decade.

Why the Bank of Japan desperately wanted inflation

But, with excessive debts in the private sector finally gone. Why did the Bank of Japan even care? I think there are two reasons.

The first is that, while the excessive debt problem in the private sector had finally been solved. The way that it had been solved, by bailing out banks, meant that now a lot of that left-over debt found itself on the government balance sheet. And while that turned out to be less of a problem than economists initially expected, deflation is still not exactly great for a highly indebted government since that debt does becomes harder to pay off as prices, and therefore taxes fall.

But, there is another important problem with deflation and that is that it rewards saving and not spending. After all, if you can buy more stuff with your money by refraining from spending it now, then people are inclined to spend less. And, that is highly problematic since an economy can only work if people actually spend their money. This is why most central banks aim for consistent mild inflation rather than complete price stability. Mild inflation helps both the private sector and government to pay off their debts while it simultaneously motivates people to spend their money rather than to hold on to it.

So okay, the Bank of Japan wanted inflation to encourage spending, but why was there still deflation? After all, this debt deflation mechanism had all but disappeared.

Why inflation remained absent

The standard theory of inflation that the central bank turned to first is the Philips curve which implies that there is relationship between inflation and unemployment. The primary idea of the Philips curve is that low unemployment simultaneously means a lot of demand in the economy and that production cannot employ enough people to meet that demand and so both wages and the costs of all goods both rise.

This is of course inflation…

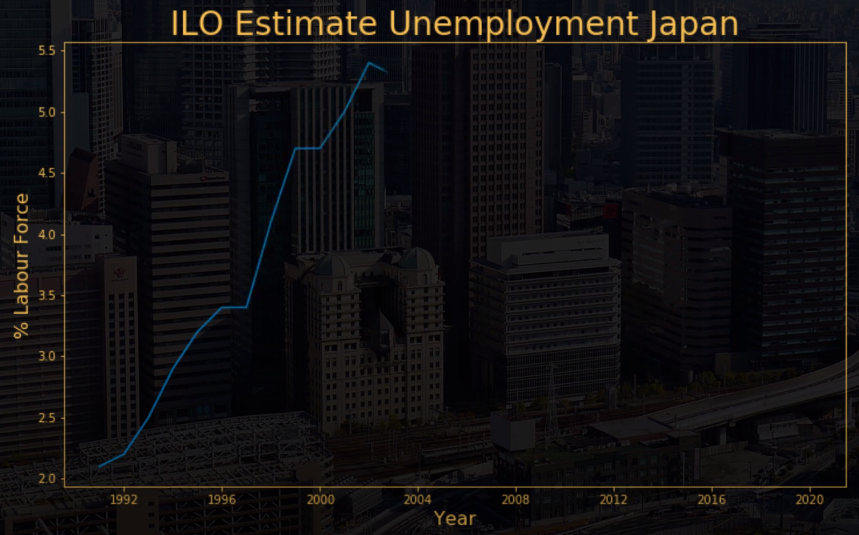

Given that supply cannot expand quickly enough, inflation, according to this theory, mostly occurs in fast growing economies. Therefore, the natural variable to look at next is unemployment during the early 2000s.

Indeed, as you can see in the graph below unemployment had risen to roughly 5%. Which was, while relatively low when compared to other countries, quite high for Japan. And, with interest rates stuck at 0%, what was the Bank of Japan to do about that? The answer is monetary experimentation.

Long after having abandoned window guidance, the Bank of Japan once again showed itself to be an innovator by starting a program that later came to be known as … quantitative easing. The main idea here was that while short-term interest rates couldn’t be much lower than zero, long-term rates, which are typically higher to compensate lenders for the increased risk of default, could be driven down further by using newly created reserves to buy bonds.

Here, you have to keep in mind that, while we now consider quantitative easing to be quite normal, at the time it was very radical.

But, considering the massive quantitative easing programs of today, there was nothing radical about the scale of these early programs. Furthermore, the Bank of Japan stressed that they would stop the program right away once deflation would turn into inflation.

And yet, while unemployment dropped… inflation did not come.

But, why not? Well, one popular explanation is that by now inflation had become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Let me explain with an example, in the 1960s Japanese inflation hovered around the 5% mark every year. So, in those years, Japanese labour unions typically demanded at least a 5% wage increase to keep up with inflation. This in turn, led to increased costs for businesses who would, to remain profitable, increase their prices by 5%. Meaning that the next year, inflation was also 5% and workers again demanded that same 5% wage increase.

As you can see, this type of inflation is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Actual inflation at the end of the year depends on inflation expectations today.

This is why, if you go through as many central bank speeches as I have done for this videos, you strikingly often come across mentions of managing inflation expectations rather than inflation itself.

However, the problem for Japan was that during the 2000s, thanks to the debt deflation in the 1990s , Japanese workers were now used to mild deflation. Naturally, they expected this to continue and by the magic of self-fulfilling expectations … it did.

In this light, it is less surprising that, during this period, the Bank of Japan was willing to experiment with something as radical as quantitative easing. It was so desperate to break through that self-fulfilling deflation cycle, that it was willing to innovate once more.

And you know what, around 2006 it seemed it to finally work, as mild inflation re-entered Japan, the Bank of Japan was confident that it could get rid of that wacky quantitative easing experiment …. and assign it to the dustbin of history.

The Global Financial crisis

And then…… the Global financial crisis hit … and Japan was hit hard. In fact, even though the financial crisis itself originated in the United States, Japans economy contracted by more than that of the United States itself.

Now, this was really unexpected. Especially since Japanese banks, still scarred from the banking crisis of 1997 had not participated too much in the global financial boom and so, they were relatively unscathed.

However, the problem was that Japan was relying heavily on exports, particularly of car exports and when demand plunged in Europe and the U.S. these sectors in particular took a massive beating.

Actually, this is quite a common problem for countries that rely heavily on exports. While it seems super safe to run consistent massive trade surpluses, it does make you very dependent on the state of the rest of the world.

But yeah, as you can imagine this was not a great turn of events for the Bank of Japan, who was still desperately trying to increase inflation expectations. And so, Japan ended yet another decade with a recession and dipped back into deflation. Sure, this time the recession was brought on by foreign problems. But, that did not make it less of a problem for the Bank of Japan.

Abenomics and Population decline: the 2010s

This also made clear to the Japanese electorate that radical change was needed… and boy oh boy did it come….

Abenomics

In 2012, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe came to power on the promise of radical economic change and the agenda that he introduced went on to be known as Abenomics.

While the jury is still out on how effective Abenomics has really been, there is broad consensus that it was quite radical..

When it was announced, Abenomics consisted of the so-called three arrows:

The first arrow was monetary policy: meaning basically a continuation of the past but amplified to the extreme. To give you an idea how extreme, consider the following propositions.

Are you interest rates stuck at zero? No problem just make them negative.

Has quantitative easing not been super effective at bringing back inflation? No problem either, you probably just did not do enough of it. How about you consider buying more or… even better buying everything.

For the Bank of Japan this meant, start buying more short term government debt, long-term government debt, corporate debt, but also, and this really unique to Japan, enter the stock market.

I mean quantitative easing in Japan has been so extreme that now the Bank of Japan owns roughly 70% of all government debt. In comparison, the Bank of England is projected to own roughly 30% of government debt after the Coronacrisis.

Also, the Bank of Japan recently announced it is willing to buy up to 15% of long-term corporate bonds. And, as a consequence of an even more radical stock buying program, they are now the single biggest shareholder of Japan, with some estimating that they own roughly 7% of the Japanese stock market. It is really hard to overstate just how radical that is given that at the start of the 21st century the Bank of Japan was really on the fence about this whole quantitative easing business.

Now, the second arrow of Abenomics was increased government spending.

On this front, Shinzo Abe promised big things as well. And indeed he did launch lots of spending packages. Under his rule Japanese government debt approached a shocking 240% of GDP, making the Japanese government the most indebted in the world.

Side-note, this is much less dangerous than you might think since most of that debt is owned by the Bank of Japan and the people of Japan.

But yeah, while it sounds like Abe was a big spender, he also increased taxes on consumption goods in 2014 and again in 2019. These consumption tax increases are particularly infamous because after each time they were implemented, the economy found itself back in recession.

And remember how the Bank of Japan was trying to shock the economy out of low the inflation expectations loop?

Well, thanks to Abe’s back and forth on fiscal spending, inflation expectations hardly moved. Not very surprising since, under Abe government the pace at which government debt increased actually decreased. So, yeah… more bark than bite on this front.

Alright, lets then move on to the third arrow of Abenomics: structural reforms. To be honest, I don’t like the term structural reforms in economics because it can mean almost anything. But, in this case it meant

- Allowing more shareholder activism to increase competition among corporations,

- Tax cuts for corporations,

- Deregulation for the corporations,

- And finally, lots of trade deals, for … you guessed it, corporations.

Now, even with broken promises on government spending, that should have been enough to re-awaken the economy of the rising sun right? Not quite, one big problem that Mr. Abe has run into when it comes to corporate Japan, is that whenever they are given gifts, such as tax cuts, they tend not to invest that money, but rather hoard it or directly turn it over to their shareholders, who then hoard it.

Since 2015, this has gotten so bad that corporations have been saving up to 5% of what they earned each year. Similarly, since then households have increased their savings by up to 4% every year.

Now, you can imagine that for the economy to re-activate and any inflation to occur, the household and corporate sector need to spend that stimulus… rather than save it. And so, not surprisingly, while inflation was definitely higher under Abe than in the previous decades, it never hit the desired 2%. Also, consumption was barely any higher at the start of 2020 than it was in 2012 when Abe entered office.

So, what went wrong?

Well for the first arrow, monetary policy, it turns out that while increasing interest rates can be highly effective at cooling down an economy, lowering rates to stimulate productive growth is much harder.

You see, there is only so much further a mature economy like that of Japan can grow. If there is no demand among firms to invest more, you can lower interest rates, but they will likely just use this opportunity to fund higher dividend pay-outs to wealthy investors with cheap debt.

You can also lower their taxes, but, similarly, how can you be sure that they won’t just pay these out in the form of dividends to shareholders? And finally, if you combine increased government spending with increased consumption taxes, it is pretty hard to expect shocking results.

Population decline

But, that being said…. There is one major theory of Japanese deflation that we haven’t talked about yet and that is …. You guessed it, demography because Japan’s population … is shrinking fast.

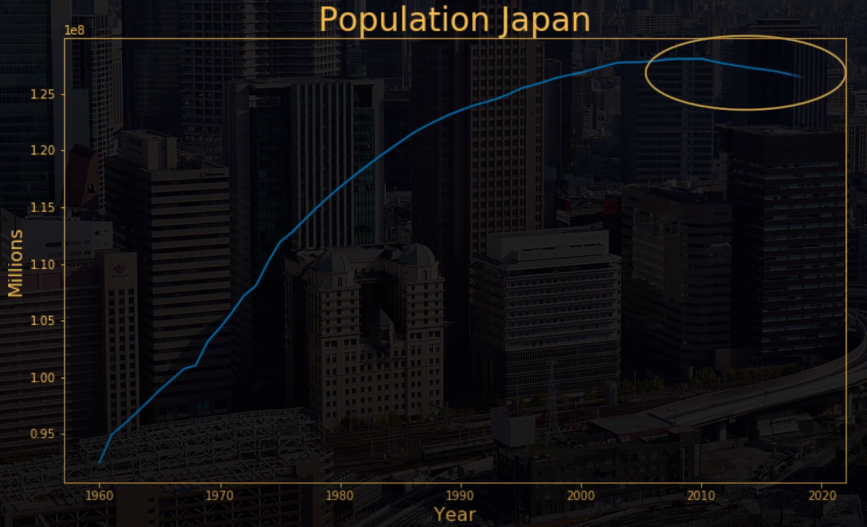

In fact, as you can see in the graph below, Japan’s population growth reversed right around when Abenomics started. This obviously had a massive impact on the economy of Japan! After all, less people working means less wage income and less demand for products, and with increased automation to replace the workers that now enjoy their pensions, no wonder deflation has been so hard to get rid of.

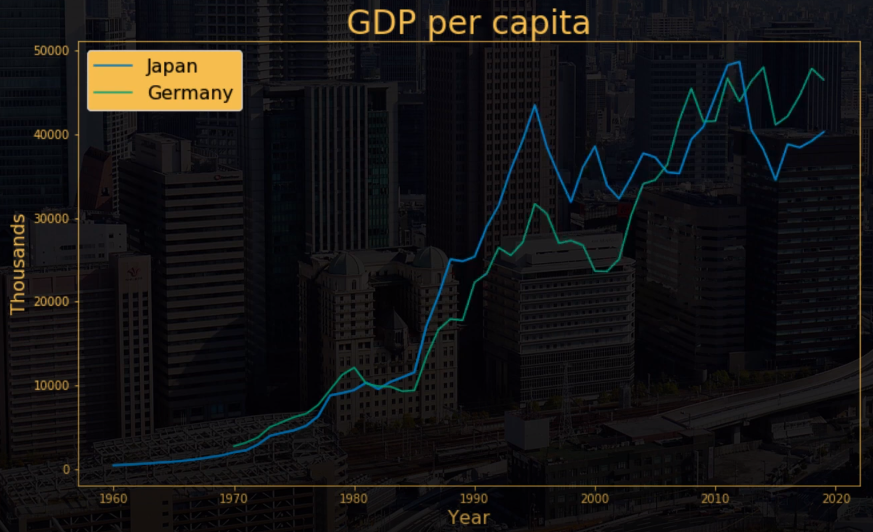

So, this made me wonder, what happens if we look at how the economy did under mr. Abe, if we correct for the shrinking population? As you can see in this graph, which shows GDP per Japanese citizen, the economic performance of Japan really hasn’t been that bad, as long as you correct for its shrinking population… If you do that, actually it has been quite similar to that of other industrialised nations.

So, it makes sense that, to truly defeat deflation, re-population policies are needed. In other words, the central bank is just out of its league here. And indeed, to fight a decreasing workforce, Prime Minister Abe tried to increase both women’s participation the labour force and fertility by building many new day-care centres and expanding parental leave. He also tried to get more immigrants to come work in Japan. For example, by making a fast track to residency for skilled workers and a guest working program for unskilled labour.

But, as leaders from Hungary to Russia to China have found out the hard way, reversing a strong demographic trend is almost impossible.

So, that left me wondering… is Japan doomed to forever remain stuck in deflation?

The future of the Japanese economy

Well, while Shinzo Abe left Japanese politics for health reasons in 2020, his party is still in power. So, it seems likely that most of his policies will continue. But, will they bring about inflation, a stronger Yen, and heavens forbid re-populate the Islands?

I very much doubt it. You see, when something doesn’t work.. the answer is rarely … well then let’s just do more of it.

So, let’s quickly go over the three arrows of Abenomics and see how they could be altered to generate some mild inflation:

Up first, is monetary policy, here we directly come across an issue that I talked about in my video on quantitative easing. Namely, if you don’t couple it with increased government spending, then all you are doing is taking one asset out of the economy and replacing it with another. This will lower interest rates on the bonds that you are taking out of course. But, it won’t give people much spending power that will generate inflation. It is more likely to lead to higher asset prices, something that will help further inflate the massive savings of Japans corporations and households but will not get them to spend and generate inflation.

So, if the Japanese government truly wants to generate inflation through monetary policy, it could consider either quantitative easing for the people (also known as helicopter money), which means that the central bank is creating money and giving it to people, or coupling massive QE with massive fiscal spending.

And, since we’ve found ourselves talking about the second arrow already, fiscal policy, the other point I want to make about that is … if you want your fiscal policy to be inflationary, then you’d better make sure that money ends up in the hand of those who actually spend it..

which are typically those at the bottom of society. Basically what Japan has found out the hard way is that if your corporations and households are already saving whatever they can, you can give them more money. But, all it does it make them save more.

Finally, let’s talk about structural reforms.

Here again, I was surprised by some of the measures implemented. Tax cuts for the corporations… those that are hoarding all the wealth and tax hikes for consumers… those that need to spend more? Why not try to do that the other way around? At least, if you want to generate some inflation.

Another, potentially more productive way to bring about inflation through increased wages is to improve the bargaining power of the Japanese worker. Structural reforms like that could even be combined with a central bank funded basic income. After all, if people don’t have to work just to survive, then that might bring about some real power to ask for increased wages to do crappy work.

And when it comes to re-population…, well this is not my area of expertise. But, I found that the most convincing explanations pointed to an insecure work environment for men and too little opportunities for women to have both a career and have babies…

But yeah, on this front, if any of you are in Japan, I would love to read your input in the comments.

Finally, while increasing immigration might help, we know from other economies that you cannot do this too rapidly without risking great social tensions. So, I’m not sure this will be the likely solution to Japans stagnation problem…

But then again, as we discussed, Japan’s economy actually seems to be doing quite well for its citizens. Its cities are beautiful and clean, its industries are still world class, crime is super low, and overall quality of life is very high.

Would it really be so bad to have a little bit of deflation?

And on the bright side, de-population might eventually lead to wage led inflation at some point as labour gets scarce and wages increase. And with the large private debts of the 90s long gone, debt deflation is hardly a risk.

Furthermore, by now, I do think that the side effects of extreme monetary policy action are getting out of hand. After all, financial markets have almost been completely taken over by the central bank. Is that something that a nation should aspire to? One part of why financial markets exist is to allocate capital to those companies that are using it productively. If the government just buys all corporate debt and most of the stock market that function is completely gone.

Sure, there are some publications out there that argue that deflation and the ageing population make government debt unsustainable.

But, think about this, over 90% of government debt is owned by the Japanese, if Japanese people die, some of the government debt they held will be transferred to their children and another portion of that will automatically be taxed thanks to inheritance tax.

When it comes to government debt, we should remember that the government is simply a construct that serves the people. And if the people own the debt of the government, this is not necessarily a burden on future generations if the holders of that debt eventually die out.

So, yeah I think the economy is not doing as badly as you might think. On the other hand, there is of course a good reason that people fret about low to no growth and that is that being young in a low to no growth economy can be pretty tough and insecure. Also, a greying population will mean that the young will have to support more and more elderly Japanese, economically speaking.

Conclusion:

But, hey that is just my outsider’s perspective on the matter. I will admit that this is purely based on my research and not my experience. As an economist, I do think that, if you truly want to understand the subtleties of the massive complex system such as the economy of a nation, you should go there and truly submerge yourself into that society.

Sadly, the pandemic has made that a bit tricky right now. And therefore, I ask you, my viewers, and specifically those from Japan, do you agree with my take? Or did I miss something?