The Danish Krone is not just the main currency of Denmark. It is also the main currency of Greenland and the Faroe islands. The Krone is issued by the central bank of Denmark (Danmarks Nationalbank). Now, the central bank of Denmark is rather unique among central banks because, rather than having the objective of controlling inflation or stabilizing the economy, its sole purpose is to stabilize the exchange rate between the Krone to and the Euro (although it states that because the Eurozone has a 2% inflation target, it also has one by extension).

But in spite of this unconventional approach, the performance of Denmark’s economy has been rather conventional… at least, compared to its northern European neighbours. Like in most of these countries, the economy has been growing at a steady pace, and inflation has been low. But, beyond this perfect exterior, there is a darker side to Denmark’s monetary economy and that is a potential housing bubble and the highest relative level of household debt amongst all rich countries. So, that begs the question, has the Krone been as properly managed?

If you prefer to consume this story in video format, check it out here:

Because the Danish central bank has such a unique focus on the exchange rate, I will start this post by checking if its currency peg to the Euro has been successful. After that, I will evaluate the record of Denmark on the more traditional monetary measures such as inflation, GDP, and unemployment. And, finally, I’ll review the monetary policies that have led to these results.

The exchange rate

The Danish Krone is pegged to the Euro such that 1 Euro should be equal to roughly 7.46 Krone’s. When the Euro was introduced, the Danes contemplated to join it .. but, in the end they did not.

This might seem strange because the idea behind both is pretty much the same: a stable currency.

And, people prefer to trade in a stable currency. That way they don’t have to worry that the price they think they got or need to pay… has changed due to exchange rate fluctuations when it is finally transferred.

A currency peg achieves this. And this makes sense for Denmark since it is a small open economy for whom exports and imports account for roughly 50% of their economy. But then you might ask… wouldn’t joining the Euro have been even better for that?

And you would right. This would have made trade even easier since then importers and exporters do not need to pay an exchange rate fee to their banks when they change currencies. But, convenience is not what motivated the Danes in this case.

Instead, the answer is … as the British would say… sovereignty … Meaning that if the Danes ever run out of money… and a run happens on their currency… they can abandon the peg. This means they wouldn’t easily get in the situation that Portugal, Spain, Greece and Ireland found themselves in during the Euro crisis… with bureaucrats from the ECB, European Commission and IMF telling them what to do, rather than them making up their own minds.

Although … if there was ever a run on the Krone, the Danes would need to be willing to adjust the peg and as anyone who has studied currency pegs can tell you, that is not always the case. For example, check out this IMF blog post on the Asian financial crisis, in which pegs played a major role.

But, yeah, so far no sign of a run on the Danish currency. As you can see, the peg between the Krone and Euro is rather stable. And that is because the central bank works very hard every day to keep it that way by adjusting interest rates and by buying and selling currency in foreign exchange markets. However, this means that the central bank does not have these tools available to fight domestic inflation like all other central banks. Although, as I discussed in my post on exchange rates, the two are connected.

Inflation

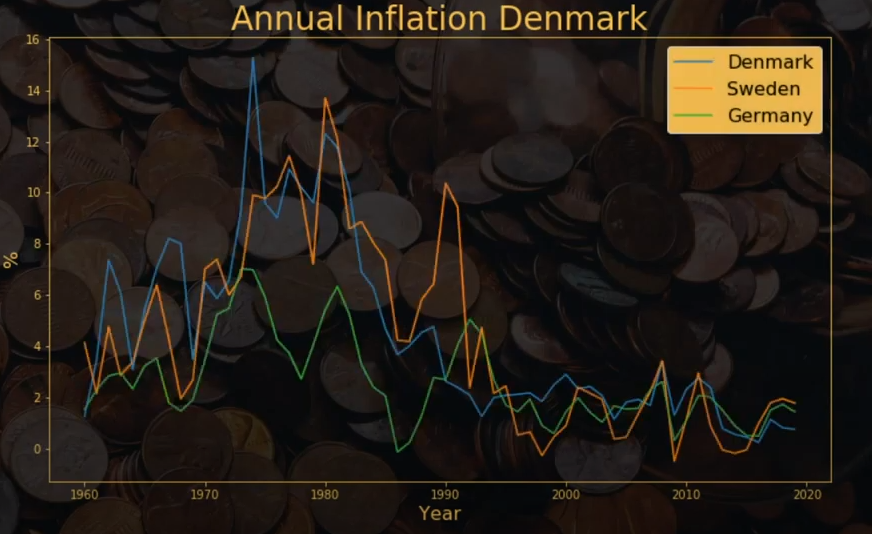

Even though the central bank doesn’t target inflation, it has been remarkably stable in Denmark and also very similar to that of neighbouring countries. For example, check out this graph of inflation in Denmark, Sweden, and Germany… Inflation has been trending downwards everywhere…

This has been quite a puzzle for central banks since their favourite theory of inflation implies that a growing economy with low unemployment should produce lots of inflation. Weirdly enough though, GDP has been growing, Denmark is one of the richest countries in world, and unemployment is at a record low. And yet, inflation has remained stubbornly low.

How is this possible?

Financial stability

Part of the answer is that some prices have actually climbed quite rapidly in Denmark.

It has just not been consumer prices and therefore has not been registered as inflation.

Don’t you love these beautiful Danish houses?

Well, you are not the only one, house prices have been notoriously bubbly in Denmark. As you can see in this chart of property prices in Denmark, they were pushed up to ski-high levels and after a little crisis dip, they are almost back to their previous highs.

Not surprisingly, Danish household debt is one of the highest in the world at around a whopping 257% of total Household disposable income. For comparison, household debt is 188% in Sweden and only 96% in big neighbour Germany (source: OECD data).

As you might imagine, this is a major headache for the Danish central bank.

But, it is not just the central banks fault for keeping interest rates at rock bottom. A major part of why Danish mortgages and house prices are so high is because politicians have been actively encouraging this and have even made mortgage interest payments tax deductible.

That being said, when looking at debt numbers like this. We do have to take into account that interest rates are indeed at an all-time low. This means that higher debt levels could be sustainable. Indeed, as you can see here,

even though debt has increased, debt service costs have gone down considerably in Denmark along with falling interest rates. That means that what looks like a bubble, might actually be sustainable… as long as interest rates stay ultra low.

Luckily for Denmark some of the other risk factors in the financial stability category are not as dangerous. One problem that every central bank is wary of is that of trade imbalances. The reason for this is that countries that import too much consistently are at risk of running out of money to buy these products and hence might see a run on their currency. This would be disastrous for the Danish Krone peg.

But no worries, Denmark, like many of its northern neighbours has run consistent trade surpluses (see OECD data and highlight Denmark) and hence has consistently seen foreign money flowing into the country via the current account.

This is bad news for the rest of the world, because if there are some countries running consistent surpluses, others have to run consistent deficits, but hey… one less worry for the central bank of Denmark, right?

And, another bright spot is that government debt seems well under control. Like many of its northern neighbours the Danes seem to have an ideological bias that underestimates the dangers of household debt and overestimates the dangers of government debt.

So, where does that leave the monetary economics of Denmark? Well, to be honest, it looks great but not sustainable.

A stable exchange rate, low inflation, and a growing economy. While it seems like a central bankers dream country at first, risks are building up in the household sector… Let’s now evaluate what the central bank is doing about it.

Monetary Policy

Like in many other European nations, the central banks main tool of the trade has been the interest rate. But to maintain the currency peg, the primary interest rate of Denmark has been negative for quite a while now.

After all, with such a massive trade surplus and hot housing market, there is consistent pressure on the exchange rate to move up beyond the level of the peg.

To discourage some of those incoming capital flows, the Danish central bank has had to lower its rates below that of the European central bank… which has rates near zero. And what is lower than zero… you guessed it negative rates.

One big problem here is that these negative rates make credit creation in Denmark extra juicy. So, it is rather tempting for local banks to blow up that housing bubble up even further.

Perhaps this is why Denmark has not yet had to embark on the large scale asset buying programs known as quantitative easing. But, with rates already negative, there are some rumours that the central bank will have to start doing so in the future if it wants to keep stimulating via monetary policy.

Conclusion.

So, now we have observed all the evidence that will allow us to answer the main question of this post. Has the Krone been properly managed?

Well, given that the exchange rate peg is secure, and Denmark’s economy is thriving, the answer is obviously yes.

However, the old way of doing things is no longer sustainable because it relies too heavily on inflating house prices, running consistent trade surpluses with the rest of the world, and having negative rates to counter incoming money from the Eurozone.

Then the question becomes, how can the Danish central bank promote a sustainable Krone?

In my opinion, the best and most radical way of doing this would be to re-evaluate the currency peg every few years. And if they do that now, the Krone would likely appreciate. This would make all Danes richer. And, at the same time, it would make Denmark less competitive and hence it would promote a trade surplus in the rest of the world for a couple of years bringing balance back to the force… economy.

A higher valued Krone, would also mean that interest rates can be brought back to reasonable levels, where they do not encourage asset bubbles. To further constrict the housing boom, Danish politicians will need to get rid of their incentives on mortgages and the central bank needs to set strict rules on mortgages and promote productive credit rather than speculative credit.

But, that is just my hot take on the matter. Do you agree? Or do you have a different take? Especially if you live in Denmark, let me know in the comments.